“Let him cry it out.”

“Don’t hold her too much or he’ll expect you to do it all the time”.

“If you coddle him too much, he’ll be a Mama’s boy”.

We’ve all heard these pieces of advice, and perhaps wondered whether we should be coddling our children less. When my girls were babies and I was wishing that they would pulleeze sleep through the night already, I considered letting them cry it out, and ultimately, I chose the method of letting them cry for 30 seconds before picking them up, to sort out which cries were based on significant issues (wet diaper, hunger, etc) and which were just those waking up cries that babies often do before falling back into a sound sleep.That was what I chose to do, and I judge no other parent for doing something different, because getting your kid to sleep feels like one of the greatest challenges on Earth. And as my girls grew, there were clearly times when they would cry for the sole purpose of getting my attention. I found myself wondering – should I pick her up? Should I teach her that she needs to self-soothe? What IS best?

We all want one main thing for our kids – we want them to turn into strong, functional adults that have the ability to effectively deal with the challenges they will face. Because let’s face it, they WILL deal with challenges. When my quite sensitive 7 year old releases a flood of tears akin to the Indonesian tsunami just because a friend doesn’t like her red shirt, I wonder…if she can’t deal with this small thing, how will she deal with a job rejection? If she can’t soothe herself after skinning her knee, how will she deal with the pain a broken arm, or a broken heart, later? What can I do to make sure she can cope? What can I do to make sure she feels comfortable in her own skin? Do I hug the living crap out of her when she’s down and show her support? Or am I actually causing her harm by doing that, since I won’t likely be standing right next to her every time she experiences pain? As parents, we don’t always know what’s best. If fact, it often feels like we never know what’s best! So my answer whenever I question what to do is to go to the science.

What happens physically when we hug our children?

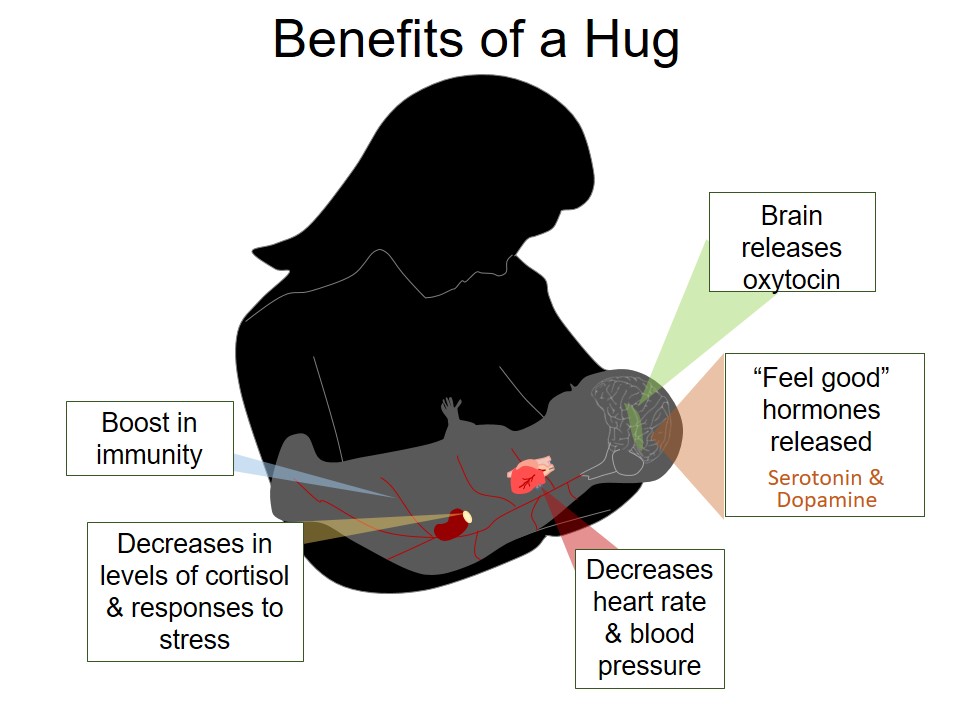

First, I think it’s important to know what a hug actually does to and for us. When someone hugs you or your child, your brain releases what’s known as “the love hormone”, oxytocin. Oxytocin is really an awesome hormone, because not only does it act to provoke feelings of love, but it also causes the release of two “feel good” hormones called dopamine and serotonin, which can act to calm you and your child and even give you a bit of a euphoric feeling. Both oxytocin and dopamine are also both really important for the bond that forms between a parent and child. Believe it or not, not all moms feel love for their babies before or even at birth. One study indicated that 27% of mothers did not feel love for their babies until the first week of life, and 8% took even longer than that to feel love for their babies. This is not because those mothers are “worse” mothers than the ones who felt the love right away. It’s because love is actually a complex physiological response that starts with the production of oxytocin and dopamine in the brain, and we are all physically different from one another, as are our birth experiences. For example, mothers that have a vaginal birth are more likely to have immediate skin-to-skin contact with their newborns after birth. This contact stimulates the release of that oxytocin, which provokes the feelings of love, stimulates colostrum production for breastfeeding, and even provides pain-relief. Several studies conducted on mommas that had C-sections indicated that when the nurses made it a point to allow skin-to-skin contact either immediately or soon after a c-section, mothers felt more bonded to their babies. Once that initial bond is formed, the benefits of hugging don’t disappear. Each time you hug your child, both of you produce oxytocin.

The benefits of a hug don’t just stop at feel-good emotions, though. There are also other physical benefits of hugging. Oxytocin acts on multiple locations in the body. It acts on the nervous system to decrease heart rate and blood pressure. It acts on the adrenal glands to decrease the production of the stress hormone, cortisol, and decrease the responsiveness of the body to stressful stimuli. Elevations of this hormone also stimulate the immune system, and help make you and your child more resistant to getting infections and illnesses. In a study published in Psychological Science, 404 participants were asked daily questions about how many hugs they had received that day. The participants were then given nasal drops containing 2 viruses that cause cold-like symptoms. Those that received more hugs each day had a significantly lower risk of becoming infected. So the immediate physical and emotional benefits of a hug are pretty clear.

But wait! There are long-term benefits too!

Did you know that the way that you interact with your child can actually alter his or her DNA? It’s true! While we all inherit our DNA well before we’re even recognizable human beings, that DNA can be modified as you progress through life. These physical modifications of the DNA can influence at what level your inherited genes are expressed and those genes determine how your body reacts to what it experiences. As a result, how you interact with your child can program his or her behavior and health well into adulthood.

Several studies conducted in rats have shown that the amount of maternal licking or grooming (the rat equivalent of hugging) a mother gives her rat pups is a very important determinant of how those pups will respond to stress when they become adults. Pups that were licked and groomed a lot had lower levels of stress hormones, and also had lower responses to stress when they became adults. In comparison, pups that experienced separations from mothers, and didn’t get the same amount of licking and grooming, grew up to be highly responsive to stressful stimuli. Scientists now know that the simple acts of licking and grooming can actually physically modify the pups’ DNA, permanently influencing the way their bodies respond to stress!

But rats are not humans. Does this actually happen in humans?

There is, in fact, evidence in humans that the level of affection babies experience can influence health in the long-term. In one study of adult men, those who ranked their parents as less loving were more likely to have chronic illnesses such as heart disease, high blood pressure, ulcers, and alcoholism. In another study of 1337 students, those who indicated a lack of closeness with parents were more likely to later develop cancer. While we don’t know whether the exact same mechanism is responsible for this programming, we do know that simple touch by a mother is enough to decrease levels of stress hormones in infants, and stress hormones are well-known programmers of physiology and behavior.

But how much is too much?

Is there a point where our children are “manipulating” us to hug them more? Well, yes! Actually, your children have been manipulating your will and even your physiology since before they were born! That is what they are designed to do! Your child essentially started out as a parasite inside of you. Developing embryos are foreign to your body and capable of manipulating your immune system to avoid attacks during pregnancy. Your baby’s DNA circulates in your blood, and your brain becomes programmed by the hormones that your baby produces. Your baby needed to do this to successfully survive and develop. What your babies/kids do once they get outside of the womb is quite the same thing. When hungry, they cry. And when they are feeling a need for affection, they also let you know that. Denying them needed affection is, in a physical sense, not all that much different from denying them food. A study in the journal Pediatrics indicated that babies that are carried more actually cried less overall. That’s because they are crying to fulfill a need. Now you might be saying, “but wait! My older child cries just to get something. That doesn’t indicate need.” True. Probably you don’t want to give in to those cries. The science I’ve mentioned doesn’t provide a roadmap for how to parent your child. But what it does say is that hugging your child and showing affection has beneficial physical and psychological effects that last throughout the child’s life. So even when you can’t offer the thing that your crying child wants, whether he or she is 6 months or 6 years old, it’s probably a good idea to offer the hug.

Contributing References

Light, K. C., Grewen, K. M., & Amico, J. A. (2005). More frequent partner hugs and higher oxytocin levels are linked to lower blood pressure and heart rate in premenopausal women. Biological psychology, 69(1), 5-21.

Douglas, A. J. (2010). Baby love? Oxytocin-dopamine interactions in mother-infant bonding. Endocrinology, 151(5), 1978-1980.

Cohen, S., Janicki-Deverts, D., Turner, R. B., & Doyle, W. J. (2015). Does hugging provide stress-buffering social support? A study of susceptibility to upper respiratory infection and illness. Psychological science, 26(2), 135-147.

Weaver, I. C., Cervoni, N., Champagne, F. A., D’Alessio, A. C., Sharma, S., Seckl, J. R., … & Meaney, M. J. (2004). Epigenetic programming by maternal behavior. Nature neuroscience, 7(8), 847.

Fish, E. W., Shahrokh, D., Bagot, R., Caldji, C., Bredy, T., Szyf, M., & Meaney, M. J. (2004). Epigenetic programming of stress responses through variations in maternal care. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1036(1), 167-180.

Glynn, L. M. (2010). Implications of maternal programming for fetal neurodevelopment. In Maternal influences on fetal neurodevelopment (pp. 33-53). Springer, New York, NY.

Russek, L. G., & Schwartz, G. E. (1997). Perceptions of parental caring predict health status in midlife: a 35-year follow-up of the Harvard Mastery of Stress Study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 59(2), 144-149.