By now, we’ve all seen the warnings about plastic bottles that contain BPA, and companies have jumped at the opportunity to sell us BPA-free water bottles, BPA-free tupperware containers…heck, there are even BPA-free toothbrushes! The overall premise of this is right – plastics are a problem. We’ve produced too many of them, we use too many of them, and we throw too many of them in the trash. In fact, the World Health Organization recently alerted us that there are microplastics in our drinking water! This presents health hazards for many reasons, and for both us and wildlife. But is a bottle that contains BPA really that dangerous? And are the alternatives really safer? When I’m at the store buying water bottles for my kids to take to school, I’m drawn to the BPA-free bottles because it seems to be common knowledge that those are the safest choices for my kids. Frankly, these days, any bottles over a dollar are BPA-free, so it’s almost hard to find ones that are not! But then, a researcher here at the University of Georgia started showing that the BPA alternative had adverse effects in his mice! So I did some searching about BPA and its alternatives, and here’s the skinny:

First, what IS BPA?

BPA is short for Bisphenol A. It’s an industrial chemical, and in the 1950s, scientists discovered that it could be used to make polycarbonate. That’s what, until recently, made up most of our plastics. Over 8 billion tons of this stuff is produced each year! Not only is it used to make plastics, but you can also find BPA in the resins that coat the inside of metallic food cans to prevent rusting, and even in the receipts that you get from the supermarket. This is because BPA is the reactive component of thermal paper that allows it to change color. In short, BPA is basically everywhere, even today in the midst of the BPA-free wave.

But in 1992, a researcher at Stanford University named David Feldman accidentally discovered that the plastic flasks that he was growing his yeast in were leaching an estrogen-like substance into the media surrounding the yeast, and he identified the substance as BPA. It was known since the 1930s that BPA could act like estrogen, but up to this point, no one knew that the BPA could seep out of plastic and into our food and water. This, of course, launched scientists into a huge effort to test the safety of BPA in our plastic products.

But what do you mean BPA acts like an estrogen?

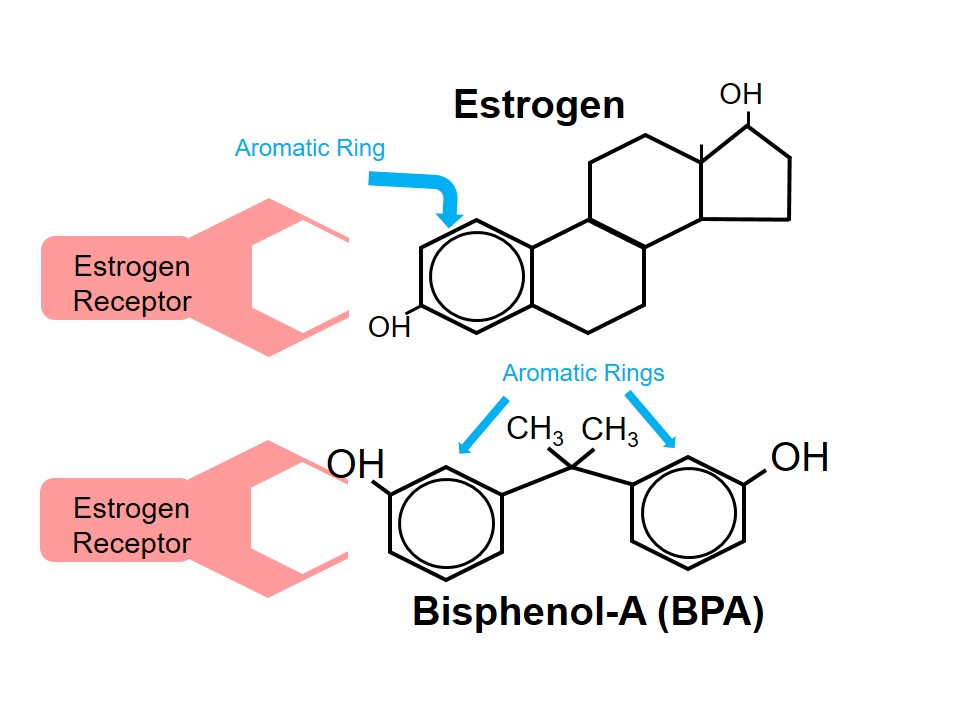

Estrogen acts on our bodies by binding to receptors that sit in many locations throughout us. In women, for example, there are receptors in our breast tissue, and when estrogen binds to those receptors, the breast tissue is triggered to grow. BPA can also bind to those estrogen receptors and thereby mimic the effects of estrogen. This is because parts of the chemical structure of BPA resemble the structure of estrogen. As you can see below, estrogen has a ring structure, and one of the most important components of estrogen that its receptors look for is called an aromatic ring. The Bisphenol A molecule has two of these rings, and these fool the estrogen receptor into thinking that it is binding estrogen. Once that happens, the receptor tells your cells to do all of the things that it would normally do in response to estrogen.

Ok, so what do we know about this?

Well, we know now that BPA leaks not only out of research flasks, but also out of baby bottles, water bottles, tupperware containers, and food cans. We know that BPA is transferred from receipts that we handle, and that it’s even passed from containers used in dairy farming into the cows and finally into our milk. It’s also in our water sources. Studies conducted in daycares and preschools have found that BPA is found not only in the water and food sources there, but also in the dust and the air! Most of us, at this point, have measurable amounts of BPA in our bodies. In fact, a CDC study of over 2500 people in 2003-2004 showed that over 92% of them had detectable levels of BPA in their urine. However, the levels that we are exposed to are still, overall, quite low. Are exposure levels actually enough to do anything to us?

So I’ll admit, when I started looking in the literature for the effects of BPA, I was skeptical that the levels we are routinely exposed were enough to cause any measurable problems. In many cases when potentially harmful chemicals are studied, researchers start with pretty large doses to see what could happen. But, as I looked through study after study, I was sobered by the overwhelming evidence that BPA not only causes harmful effects in almost all types of animals studied, it has influences on many different parts of the body (almost too many to count!) and, most importantly, seems to work best (yes, I said best!) at low doses!

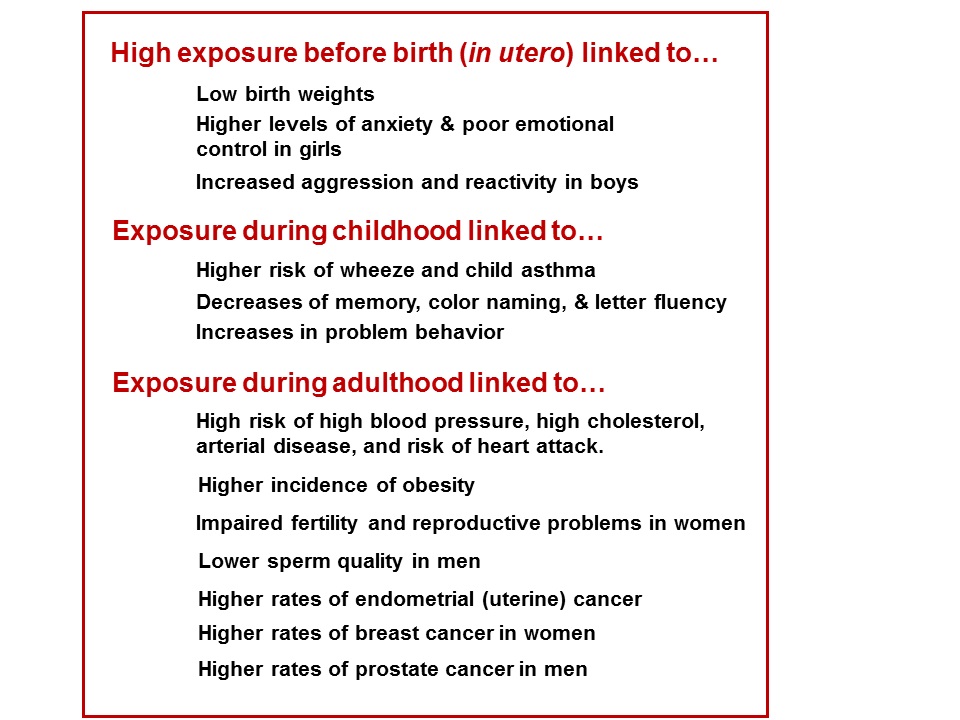

There were even two studies showing that kids who got tooth fillings containing BPA performed worse on memory tests, color labeling, and word recognition tests! And what’s more, we now know that babies developing in the uterus are extremely sensitive to hormones like estrogen, and, it seems, to chemicals like BPA. So while small amounts in adult humans may not be enough to affect us, exposure of our developing babies and even our growing children, may be what we really have to worry about, because exposure to hormones and hormone-mimics like BPA during development can organize and program our children’s health for the rest of their lives. Below is a list of just some of the research done showing links between BPA and adverse medical outcomes in humans:

OK, so what does this mean for BPA?

If you’ve read my flu shot post, you’ve heard me rail against fear mongering. I don’t believe that it’s the job of a blogger to scare you away from getting a shot, eating a genetically modified food, or drinking your water from a bottle that has BPA. Usually, I try to approach my posts from the other side, to diffuse much of the unwarranted fear that’s generated by new technologies or false ideas that are floating around out there. But in this case, it’s pretty clear that BPA is some nasty stuff. And the reality is, we can reduce the amounts we take in, but we can’t eliminate it, at least on our own. So what can you do to reduce the BPA you’re exposed to?

- Don’t heat your food or drinks in bottles or tupperwares made with BPA. In plastic products that you use every day, BPA generally won’t leak out unless the plastic is heated. In a study published in the Journal of Environmental Science and Health, researchers tested the milk in 11 baby bottles. Milk from four of them had measurable amounts of BPA, and those bottles had been heated either in the microwave or with a bottle warmer. If you need to heat your food or drink, transfer it to a container without BPA.

- Refuse paper receipts at the store, and get electronic receipts instead. Not only are you reducing your BPA exposure, but you’re also saving a tree or two!

- Choose fresh vegetables over canned veggies, and if you choose canned veggies, wash them well to remove any residual resin before heating.

- If you’re pregnant, try your best to avoid plastics, handling receipts, and eating canned foods altogether.

- Support centralized efforts to reduce the amount of plastic we use overall.

What about using BPA-free products?

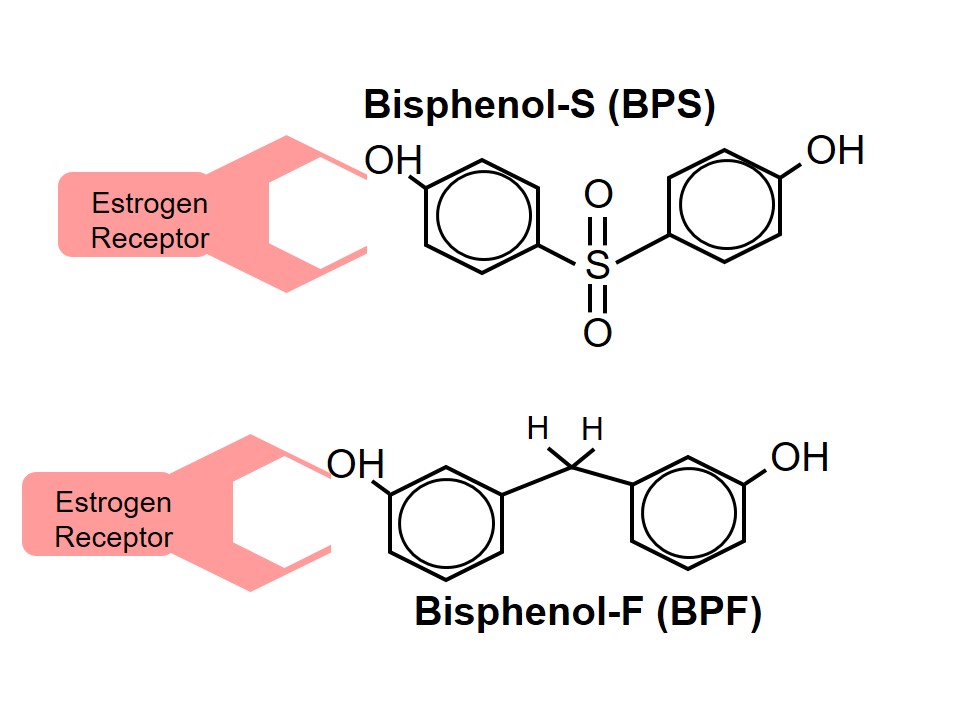

You’ll notice that this is not number 1 or even number 5 on my list. In fact, it’s not on my list at all. That’s because the manufacturer’s of BPA-free products are basically trading one chemical for another, and the replacement could potentially be even more toxic than the original! Most BPA-free bottles contain either Bisphenol S (BPS) or Bisphenol F (BPF). Check out the structures of those:

Notice anything? The rings are still there! In fact, manufacturers haven’t really been able to come up with an easy and affordable way to make plastic without them, so for now, if you’ve got plastic, you’ve probably got one of these compounds in it. What’s more is that so far, there have been over 50 studies showing that both BPS and BPF are just as potent and act in similar ways compared to BPA, meaning that they mimic estrogen and can cause effects even at lower levels.

Most of the study approaches examining effects of BPS and BPF are where the BPA studies were a decade ago – focusing mostly on mouse and rat systems. But so far, those studies are showing the same patterns in rats and mice that we saw in BPA studies on rats and mice, studies that preceded the finding of similar effects in humans. And we now know that BPS and BFP also leach out of plastics just like BPA does. In fact, BPS is already in our water sources, and detectable amounts have been found in some human populations as well. As an endocrinologist, I can tell you that, based on the many studies already out there, there is every reason to believe that in a very short period of time, we will start seeing evidence that BPS and BPF cause just as many adverse effects in humans as BPA does, and manufacturers will be looking for something safer to make their plastics with.

So what do we do now??

Much to my chagrin (and probably yours too), my reading has basically told me that plastics containing BPA are probably dangerous, especially to growing children, and that the “non-BPA” alternatives are not likely any better. But as parents, we know that handing a drink in a glass to a clumsy toddler and serving our kids food on china, is a recipe for disaster! If we really sit and think of all the plastic we use, it seems quite daunting to do without it. We give them straws so they don’t tip their drinks over (though there are some really cool reusable straws you can buy cheap on Amazon and they even come with their own cleaner!). We send them off to school with baggies full of snacks. And for Christmas, we hand them toys (like LOLs!) wrapped in layer upon layer of plastic, the opening of which is probably the most enjoyable part. How can we possibly eliminate plastics from our lives?

The answer is, at this point, to do what we can. Giving kids cold drinks in plastic cups is not likely to give them much if any BPA, BPS, or otherwise. Ditto cold foods in plastic containers or bags. But what we really need to be thinking about is the broader picture. In the immediate sense, all we can really do is avoid heating up the containers. But we need to be thinking in a broader context. When these plastics go into the trash can, they end up in our lakes and rivers, where they are exposed to the hot sun, and contaminate the water we drink and the fish we eat. This is harmful not only to us, but also to the wildlife living in those lakes and rivers, and animals that eat the fish in those lakes and rivers.

So what can we do? We need to think outside the box. We need to support research aimed at coming up with alternatives to plastic bottles and containers (like these awesome edible water bottles!). We need to recycle the plastics that we do use, and we need to support government-funded programs that monitor levels of these contaminants and their effects on humans and wildlife. There’s even a very cool company called 4Ocean that will remove one pound of ocean plastic and send you a bracelet for $20.

There was a quote I saw on Pinterest that I really liked:

“’It’s only one straw’” said 8 billion people.”

Every one of us can make a difference with small steps each day. In this case, we are fighting for the health of our children, and of theirs. Using cold plastic will only get us so far. Reducing our plastic usage and waste is the only thing that will reduce our exposure to these toxic chemicals. Here’s what you can do now:

- Use reusable straws and silverware

- Use reusable grocery bags. They actually hold way more than plastic bags and have many other uses too!

- Recycle the plastic you DO use.

- Use a reusable metal water bottle during the day.

These are all simple things, but they will both help decrease your own BPA, BPS, and BPF exposure, and also decrease the amount going into the environment, and as a result, our water sources.

Contributing References:

For an excellent summary of BPA studies conducted on humans, check out:

Rochester, J. R. (2013). Bisphenol A and human health: a review of the literature. Reproductive toxicology, 42, 132-155.

Russo, G., Barbato, F., Cardone, E., Fattore, M., Albrizio, S., & Grumetto, L. (2018). Bisphenol A and Bisphenol S release in milk under household conditions from baby bottles marketed in Italy. Journal of Environmental Science and Health, Part B, 53(2), 116-120.

Krishnan, A. V., Stathis, P., Permuth, S. F., Tokes, L., & Feldman, D. (1993). Bisphenol-A: an estrogenic substance is released from polycarbonate flasks during autoclaving. Endocrinology, 132(6), 2279-2286.

Hormann, A. M., Vom Saal, F. S., Nagel, S. C., Stahlhut, R. W., Moyer, C. L., Ellersieck, M. R., … & Taylor, J. A. (2014). Holding thermal receipt paper and eating food after using hand sanitizer results in high serum bioactive and urine total levels of bisphenol A (BPA). PloS one, 9(10), e110509.

Calafat, A. M., Ye, X., Wong, L. Y., Reidy, J. A., & Needham, L. L. (2007). Exposure of the US population to bisphenol A and 4-tertiary-octylphenol: 2003–2004. Environmental health perspectives, 116(1), 39-44.

Rubin, B. S. (2011). Bisphenol A: an endocrine disruptor with widespread exposure and multiple effects. The Journal of steroid biochemistry and molecular biology, 127(1-2), 27-34.

Vandenberg, L. N., Hunt, P. A., Myers, J. P., & vom Saal, F. S. (2013). Human exposures to bisphenol A: mismatches between data and assumptions. Reviews on environmental health, 28(1), 37-58.

Rochester, J. R., & Bolden, A. L. (2015). Bisphenol S and F: a systematic review and comparison of the hormonal activity of bisphenol A substitutes. Environmental health perspectives, 123(7), 643-650.

Žalmanová, T., Hošková, K., Nevoral, J., Prokešová, Š., Zámostná, K., Kott, T., & Petr, J. (2016). Bisphenol S instead of bisphenol A: a story of reproductive disruption by regretable substitution–a review. Czech Journal of Animal Science, 61(10), 433-449.

Parental exposure to BPA in the workplace was associated with decreased birth weights.

Miao, M., Yuan, W., Zhu, G., He, X., & Li, D. K. (2011). In utero exposure to bisphenol-A and its effect on birth weight of offspring. Reproductive toxicology, 32(1), 64-68.